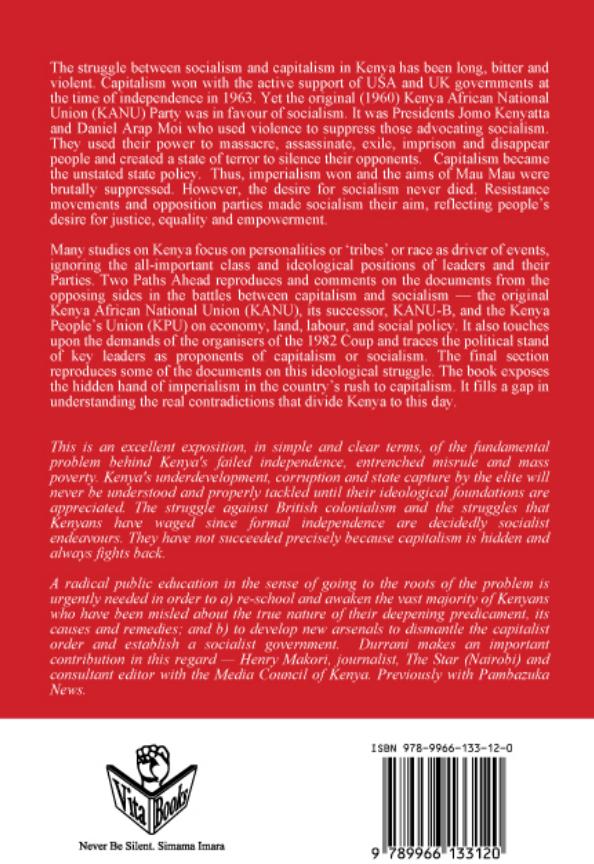

Shiraz Durrani (2023): Two Paths Ahead in Kenya. The Ideological Struggle between Capitalism and Socialism in Kenya, 1960-1970. Nairobi: Vita Books.

Available at: https://www.africanbookscollective.com/ books/two-paths-ahead

Shiraz Durrani’s book, Two Paths Ahead is a crucial work to understand the tragedy of an African liberation being stolen and degraded to the benefit of a new African ruling class. This was to the satisfaction of British imperialism, which wanted to keep its key position in support of the white settlers and capitalism.

Kenya was part of the British Empire and in 1963 it became an independent republic. The book documents the long struggle for freedom and land before independence and after. It uses and reproduces key documents from the main conflict between capitalism and socialism. The treason of the new black bourgeoisie is revealed: Imperialism was able to take the air out of the liberation by using all kinds of violent and dirty tricks.

Socialism was popular after the Second World War and workers and peasants wanted a people’s republic with nationalisation of land, free education and health. But the white settlers were not willing to give up their privileges in the form of stolen fertile land and control of the state. For the local people, expulsion from their lands and being reduced to servants of the white rulers meant that there were constant rebellions against this tyranny. This land-grabbing was systematic and the Pan- Africanist WEB Du Bois wrote about this as the Africans in the 1920s protested the land-grabbing by the British colonialists. In the book The New Negro: An Interpretation by Alan Locke (1927):

Here was a land largely untainted by the fevers of the tropics and here England proposed to send her sick and impoverished soldiers of the war. Following the lead of South Africa, Britain took usurped five million acres of the best lands from the 3,000,000 native inhabitants, herded them towards the swamps giving them nothing as compensation, even there, no sure title; then by taxation the British forced sixty per cent of the black adults into slavery for the ten thousand white owners for the lowest wage. Here was opportunity not simply for the great landholder and slave-driver but also for the small trader, and twenty-four thousand Indians came. These Indians claimed the rights of free subjects of the empire—a right to buy land, a right to exploit labor, a right to a voice in the government now confined to the handful of whites. Suddenly a great race conflict swept East Africa—orient and occident, white, brown and black, landlord, trader and landless serf. When the Indians asked rights, the whites replied that this would injure the rights of the natives. Immediately the natives began to awake. Few of them were educated but they began to form societies and formulate grievances. A black political consciousness arose for the first time in Kenya. Immediately the Indians made a bid for the support of this new force and asked rights and privileges for all British subjects—white, brown and black. As the Indian pressed his case, white South Africa rose in alarm. If the Indian became a recognized man, landholder and voter in Kenya, what of Natal?

The British Government speculated and procrastinated and then announced its decision: East Africa was primarily a “trusteeship” for the Africans and not for the Indians. The Indians, then, must be satisfied with limited industrial and political rights, while for the black native—the white Englishman spoke! A conservative Indian leader speaking in England after this decision said that if the Indian problem in South Africa were allowed to fester much longer it would pass beyond the bounds of domestic issue and would become a question of foreign policy upon which the unity of the Empire might founder irretrievably. The Empire could never keep its colored races within it by force, he said, but only by preserving and safeguarding their sentiments”.

Tired of the humiliations, a more open liberation struggle against the British started with the so-called Mau Mau. The British tried by propaganda, splitting and harsh repression, like hanging, to subdue the militants.

The rebellion, also called The Land and Freedom Army, gave hope to millions of Africans tired of the foreign rule of white racism. The settlers also turned to psychiatry to reduce it to “an irrational force of evil, dominated by bestial impulses and influenced by world communism”, according to Carothers (1947). They used not only racism, reducing the fighters to the status of animals, and claimed it was a battle between the ‘civilised’ against the ‘uncivilised primitives’. This was a cold war rhetoric to gain support from white racists and imperialism.

The colonial narrative placed Jomo Kenyatta in an important role. Kenyatta became a willing tool of the British and was able to sideline his opponents who wanted justice and land reform. He was able to profit by becoming a big landowner and using the tribal card of divide and rule to privilege his own tribe and loyalists with positions and land. The party, KANU (Kenya African National Union), was divided on ideological grounds on the future of a liberated Kenya. British intelligence was hard at work to corrupt the incoming African politicians and Kenyatta, who the British had earlier imprisoned, became their favourite. The opposition, with people like Pio Gama Pinto and Oginga Odinga, challenged the land and money-grabbing they could see. Pinto became a key enemy for the new rulers and was brutally assassinated in 1965. This was a hard blow for the socialist collective that Pinto was part of. KPU (Kenya People’s Union) was formed in 1966 as a protest against Kenyatta and his capitalist policies. Imperialism tried to reduce the struggle to a tribal warfare or a struggle between personalities, but for the first time in Kenya, a political party, openly advocating socialism, was formed. In 1969, the Kenyatta government banned KPU and arrested its leaders.

One of the tricks of Kenyatta was to talk of his policy as an ‘African Socialism’. The KPU Manifesto (p.194) from 1966 talks about this ‘African Socialism’ as a meaningless phrase and a cloak for the practice of total capitalism, promoting the development of a small, privileged class of Africans. This led to the control of the economy by foreigners growing every day and without any nationalisations. This was in contrast to socialism’s basic principles on equality in the distribution of income, control over the means of production and the minimisation of foreign capitalist control of the economy. KPU put the finger on the fact that ministers owned big estates, and demanded that land be available for the Wananchi (the masses). Durrani sees the murder of Pinto as crucial in the class struggle for Kenya`s future. KPU’s Wananchi Declaration of 1969 says more clearly that the people wanted their land returned to the owners and that they wanted all Mau Mau fighters to be restored to their land, which they had fought for. They wanted economic and social changes, fulfilling KANU´s earlier pledges to the people. This progressive nationalism was met with terror and arrests, to the delight of the British settlers and imperialism. One of the more shocking details in Durrani’s book is the scorn and contempt that Kenyatta expressed, shortly after his release from prison:” ‹At Githunguri, an African-run Teacher Training school turned into a butchery during the revolt, where over one thousand Kikuyu were hung by the British forces of law and order, Kenyatta referred to the Mau Mau as `a disease which has been eradicated and must never be remembered again`”(p.178).

Kenyatta made deals with the British that forced people to take loans if they wanted to buy their stolen land back. He created a system whereby he and his loyalists profited and installed a regime where looting, land-grabbing and corruption became systemic. Market principles with the ‘willing buyer/ willing seller’ were introduced — a disgrace to the freedom movement where land rights had always been at the very heart of the struggle. Kenyatta was giving himself and his loyalists the same privileges for land grabbing as the British. The rights of the British Governor were transferred to the President, and destroyed the prospect of a more just and equal Kenya.

This was a betrayal that continues to this day, as the class struggle in Kenya to a high degree concentrates on the land issue, see Klopp & Lumumba (2017), who argue “that post-colonial elites never fundamentally reformed a system of land expropriation for the few and powerful. The challenge for reformers is to overcome these powerful forces arrayed against change with creative mobilisation strategies”.

Kenyatta was chosen and picked by Britain to ensure their interests, but USA was also involved in promoting the acceptance of capitalism and Western economic interests. The activist trade union movement had to be controlled and here Tom Mboya played a crucial role (p.130). Through him, the CIA poured money into the country to support capitalism and at forming an African elite against the demands from the people who wanted to break the chains of colonialism. Susan Williams (2021) documents this in her important book: White malice. CIA and the covert neocolonisation of Africa.

Two Paths Ahead brings justice to the brave people of the Land and Freedom Army and to people like Oginga Odinga, Pio Gama Pinto, Bildad Kaggia, Makhan Singh and many others fighting for justice and socialism. It also contains central documentation on their political position.

Thanks to Shiraz Durrani and Vita Books for publishing this important book. It needs to be widely read by the young people of Kenya in the struggle against capitalism and imperialism.

References

Jaqueline M. Klopp and Odenda Lumumba (2017): ‘Reform and Counter-reform in Kenya`s Land Governance’. Review of African Political Economy, Vol. 44, No. 154, 577-594 (2017).

Du Bois citation is from Wikipedia Kenya Colony – Wikipedia, citing:

Du Bois, WE Burghardt (1 April 1925). ‘Worlds of Color’. Foreign Affairs. Vol. 3, no. 3. ISSN 0015- 7120. (1925).

‘The Negro Mind Reaches Out’. In Locke, Alain LeRoy (ed.). The New Negro: An Interpretation (1927 ed.). Albert and Charles Boni. pp. 404–405. LCCN 25025228. OCLC 639696145.

Carothers, John Colin cited in Mau Mau rebellion – Wikipedia

Williams, Susan: White malice. CIA and the covert neocolonisation of Africa (2021),New York, Hurst.