Reviewed by Lena Anyuolo

Amrit Wilson first wrote Finding a Voice: Asian Women in Britain in 1978. This expanded edition is the second publication of the original. It contains reflections of women who read the book forty years after its publication in 2018. Wilson wrote the book to counter the colonial and racist anthropological lens used then to view Asian women. The material used to build the patriarchal perspectives was gathered from interviews of Asian men about their wives, but never the women themselves. Some of the stereotypes about Asian women, such as then notion that Asian women have a higher pain threshold, were used to justify and inform British government policy.

As a journalist and activist, Wilson felt compelled to show an alternative and realistic perspective of Asian women’s lives as told to her by Asian women, to counter the mainstream racist construction of the women in her community.

Using interviews with women on various subjects such as immigration, the workplace, marriage, education, family life and political struggles, Wilson challenges us to analyse critically how attitudes and relationships between genders from the past dominate and haunt the present. She poses questions relevant in all societies like “What are oppressed and exploited women to make of women’s rights, and the freedoms accorded to them in the 21st Century?” and “Has the role of women as the reproducers and servicers of the labour force changed or are women still slotting themselves into the different patriachies in their families and workplaces?”

What is also clear throughout the book is the intersection between race, class and gender and how the three cannot be delinked from the political reality of people of colour. For example, in the chapter on ‘Work Outside the Home’ she documents the struggles of Asian women in the factories. This group of women was paid the lowest amount of wages in the factories in Britain. The employers used the stereotype that Asian women were passive and submissive to justify that exploitation. Asian women did not have representatives in the labour unions. A Caucasian woman was placed in their stead. They were also betrayed by the bureaucracy of the labour unions when they tried to strike. Inspite of these obstacles, the Grunwick Photo-Processing strike carried out by Asian women to protest against poor working conditions was the most successful strike of the 70s. This victory had great influence and impact on other Asian women in the industrial sector. It gave them the courage to stand up and demand for their rights.

In the chapter on ‘Adolescence and Sexuality’, Wilson analyses the complicated nature of freedom. She argues that when South Asian women began to chart out their own path,as depicted in their choice of love relationshiops or even in the type of clothes they wear, they were viewed to be threatening the family’s izzat or honour. Izzat is linked to the man. It is her father, husband, brother and uncle whose ego will be hurt. The consequences of that dishonour are ostracization from the family and worse still, their mother and aunties were made to carry the blame. Wilson finds that women who break from the family’s armlock also have to cast out its embrace. Womanhood was defined and regulated principally from the purview of male dominance.

The oppessive nature of dowry and how it fits neatly into class soceity is also discussed by Wilson. Daughters are seen as a burden because of this. The groom’s family may ask for high amounts of money and gifts and the brides’s family is forced to oblige as the amount of dowry paid can make the family move higher or lower in the cast system.

Reading the chapter on Immigration against the backdrop of rising fasicm in Europe, the election of Boris Johnson in the UK and the heightened British nationalism during the Brexit debate, was a chilling experience. The immigration laws in the 1970s were racist and the trend has been continued in Theresa May’s Immigration Acts of 2014 and 2016 . These led to the mandatory surveillance of people of colour who have immigrant status. Wilson shows how racism has been intricately woven into the social fabric of British soceity through its institutions such as Immigration services which carry out forced sexual examinations of Asian women and detains them in the most inhumane conditions, regardless of their health. The story of Zubeida who went into labour during detention without any assistance, and the consequent loss of her child is enough to send the reader into a fit of rage. Moreover, essential public institutions such as hospitals do not have Punjabi, Gujarati or Hindi transaltors to meet the language needs of South Asian women.

Wilson also writes about the beautiful examples of intimacy and friendship among women and how these bonds help them navigate, interpret and fight racism, class and gender oppression. Truly, in the solidarity and sisterhood of women at the Grunwick picket line, or in animated afternoons in each other’s living rooms, the warmth and resiliance of women persists..

What I have drawn from reading this book is that to counter the dominant sexist narratives of ‘model’ women in any space, one must document continously acts of women’s resistance in order to preserve the radical history of black women which is in danger of being forgotten or revised by neoliberal feminism. It is also a challenge to see myself outside the boundaries of how a woman should and shouldn’t behave in any space, as the women in this book have. The most important thought after reading the book is that I am not alone, that despite the multiplicities of narratives shared in this book, the struggle against all forms of domination — patriachy, racism and capitalism — is a worldwide struggle in which all the oppressed women – and men – join hands to defeat the unjust system.

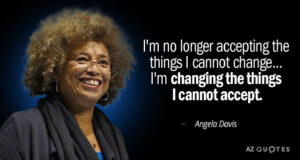

Angela Davis

“Feminism involves so much more than gender equality. And it involves so much more than gender. Feminism must involve a consciousness of capitalism (I mean, the feminism that I relate to. And there are multiple Feminisms, right). It has to involve a consciousness of capitalism and racism and colonialism and post colonialities and ability and more genders than we can even imagine, and more sexualities than we ever thought we could name.”

“As a black woman, my politics and political affiliation are bound up with and flow from participation in my people’s struggle for liberation, and with the fight of oppressed people all over the world against American imperialism.”

“We have inherited a fear of memories of slavery. It is as if to remember and acknowledge slavery would amount to our being consumed by it. As a matter of fact, in the popular black imagination, it is easier for us to construct ourselves as children of Africa, as the sons and daughters of kings and queens, and thereby ignore the Middle Passage and centuries of enforced servitude in the Americas. Although some of us might indeed be the descendants of African royalty, most of us are probably descendants of their subjects, the daughters and sons of African peasants or workers.”

Taken from various sources