The year is 1976. The nation is in the iron grip of a powerful KANU (Kenya African National Union) elite which tolerates no opposition to its tyrannical rule, nor any resistance to its antipeople policies. Anyone who dares to challenge the all-powerful armed might of the minority elite in power is detained, jailed, exiled, eliminated or disappeared. Those eliminated in early years of Uhuru for opposing land grabs and stealing of national wealth had included General Baimunge and Pio Gama Pinto (both 1965, see ‘Biographies’, below). JM Kariuki suffered the same fate in 1975. An overview of that year is provided by Carol Sicherman,1 indicating the political situation in the country:

1975 (March): Disturbances follow assassination on 2 March of JM Kariuki; during student clashes with police, students are raped, nearly 100 students arrested, and dozens hospitalised …. 28 May: University of Nairobi closes following student disturbances …. 15 October: Martin Shikuku and Jean Marie Seroney, opposition MPs, are detained, gun being drawn on Seroney. On 16 October [President] Kenyatta warns his critics: ‘People seem to forget that a hawk is always in the sky ready to swoop on the chicken.

In such an oppressive situation in 1976, the mass media dared not question the dictates of the regime. The looting of peasant land by ‘legal means’ was the order of the day. Key sectors of the economy were farmed out among the ruling elite, backed by murder gangs and the GSU2 paramilitary force. Starvation, landlessness, unemployment and homelessness were the reality for working people. The key demands of Mau Mau – return of land, free education, medical care, freedom and political power – became distant dreams.

All avenues of protest were blocked. No party but KANU could be registered. Peasants could not complain about their stolen lands and unfair returns; workers had no militant trade unions – like the East African Trade Union Congress under Makhan Singh or the militants in the 1950s who introduced working class ideology to Mau Mau – which could represent their economic and political rights; professionals, civil servants, students, indeed nobody, had constitutional rights to life and liberty anymore. Life itself became a gift from the ruling class, not a right.

History books were closed, historians silenced. The regime felt threatened by the calls for socialism, justice and equality, fearing it could destroy the status quo. The aims of Mau Mau would destabilise the neo-colonial ‘peace’ for the elite. Armed resistance to colonialism and capitalism could not be mentioned. For what would happen if the same methods were used today? ‘Forgive, and forget history’ became the daily mantra from the ruling elite. We all fought for Uhuru, it claimed, even when homeguards who fought against the people and for the colonial masters were rewarded with state power. It was the time of torture, massacres and violent death. ‘Follow what you are told or face the GSU’ was the elite’s message to the restless youth seeking justice. The country was turned into a prison without walls for the working class.

But wait. All is not silence. Resistance is taking root again as it must under all repression. Underground resistance is awakening once more. A forthcoming article3 by Kimani Waweru and myself looks at the growth of this resistance:

Most of the open spaces to express discontent were shut down …. In 1975 resistance regrouped and formed an underground party, the Kenya Workers’ Party4 . The party took a leftist stand and operated in utmost secrecy. Knowing too well that the people who were to bring genuine change were workers and peasants, it endeavoured to reach them and to learn from their experiences. They were the resistance, the real workers’ party. It connected with working people through cultural activities. The most famous of their activities was theatre, and an example of this was Ngugi wa Thiong’o’s play Ngaahika Ndeenda (I will marry when I want), which was performed in Limuru by peasants and workers. The play depicted the struggles of peasants and workers.

Recognising its power, the government of the day banned it and detained the writer. The detention of opponents of the ruling regime was the order of the day during the seventies. Among those who were detained were Koigi wa Wamwere, a young MP at the time, deputy speaker of the National Assembly Jean Marie Seroney, another vocal MP, Martin Shikuku and George Anyona, among others.

The December Twelve Movement (DTM), successor to the Kenya Workers’ Party, set out its ideological position. It became active in the three areas that were essential in any resistance movement: political, economic and cultural activities. It established study cells and linked its theories with practice. It was active in trade unions and started working with workers and peasants in their struggles. It radicalised professional bodies. It realised the importance of information and communications and published an underground newspaper, Pambana5 . It also established a library underground, many of which books are in the Ukombozi Library today (see box). It was actively researching and publishing historical material. It was also active on many of the sorts of cultural front recently outlined by Len WMcCluskey6 in the British context:

There is another struggle, though – the cultural struggle. And culture is not just the arts, it is all the things we do to entertain, educate and enlighten ourselves, usually with others. It includes the arts like music, films, theatre and poetry.

As was the practice with all of DTM’s work, its cultural policy and practice was influenced by theories from other revolutionary situations in Africa and elsewhere, such as the Soviet Union, China, Cuba and Vietnam. Particularly important was the use in its study sessions of Mao’s Talks at the Yenan Forum on Literature.7 At the same time, it circulated underground the history of Kenya from working class perspective and its vision of the society it was aiming for. This was later published as InDependent Kenya.8

DTM cells organised different types of activities, in different languages at different times. For example, they produced a children’s play, Amaro Desh, Kenya (Our Country, Kenya) in Gujarati with child actors and actresses. Plays it produced included Portraits of Survival and Kinjikitile – Maji Maji [see Box 1]. Another activity was the showing of progressive films to workers and peasants, as I have recorded:9

Among its early ventures was the showing of progressive films to workers and peasants in a semi-rural area just outside the city. The shows were organised by Sehemu [see Box 2] as part of the work of the Kabete Library serving the Faculties of Agriculture and Veterinary Science of the University of Nairobi at the Kabete Campus, about 16 km from the city centre. The film shows were held in the lecture theatre at the campus and took place in 1981. This was an important departure for the progressive librarianship movement from the conservative service in Kenya in a number of ways. The use of film shows as a way of meeting information and learning needs of local communities was one such departure. Another was the fact that the doors of a major academic institution were opened for the first time to a non-academic – worker and peasant audience. But perhaps the most significant point was the content of the films. Three films were shown in the Black Man’s Land trilogy: White Man’s Country, Mau Mau and Kenyatta. These were produced and directed by Anthony Howarth and David R Koff and were written by David R Koff. The significance of showing these films was that they were frowned upon by the KANU Government at the time and even the normal showing of the films was extremely difficult, if not impossible.

DTM also encouraged its members to write plays, short stories and poems. Some poems were carried in Pambana. A collection of resistance poems was circulating underground and is to be published by Vita Books in 2019 under the title Tunakataa! (We Say No!). Kenyan history has failed to record not only the achievements of Mau Mau but also resistance to neocolonialism, capitalism and imperialism after independence. This includes the work of DTM in different fields. It is not surprising that the KANU-Moi government sought to eliminate DTM as it saw the real danger posed to the comprador rule, particularly as DTM mobilised thousands at its cultural activities.

Kenyan History Through Carvings

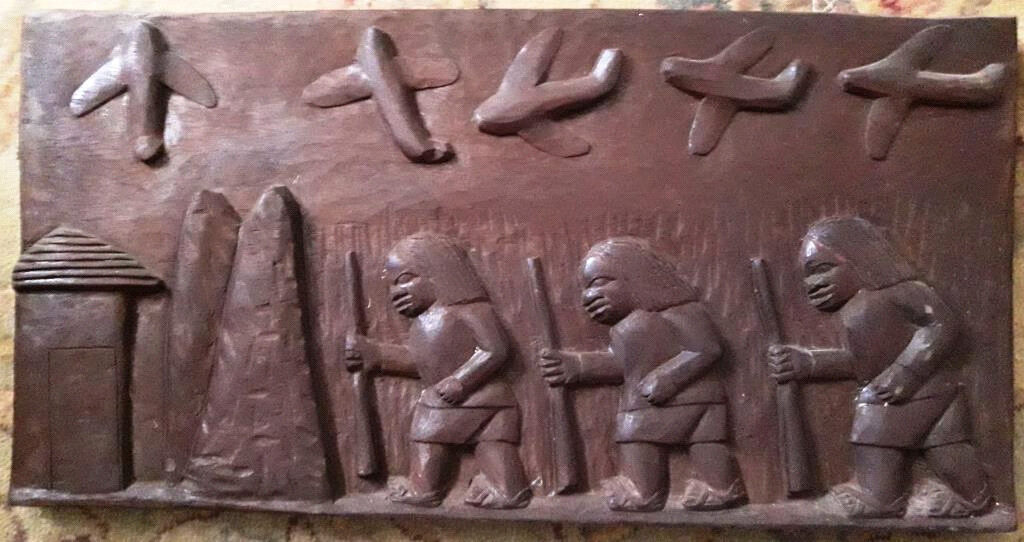

It was in this climate that a group of Wakamba wood carver artists, with the support of DTM activists, began to study Kenyan history. This was not easy, as few books on Mau Mau and the struggle against colonialism and imperialism were available. DTM’s underground library filled the gap. The carvers’ deep research revealed Mau Mau’s real history and contribution to the war of independence. They then told Kenya’s history by carving key scenes onto wood carvings. There were 36 carvings in all. The artists created multiple copies of the complete set which soon became collectors’ items among DTM members and supporters. The entire collection was on exhibition for a month at the YMCA (Young Men’s Christian Association) Cottage Crafts, Nairobi in 1976 and attracted thousands of students and workers.

As the exhibition did not attract mainstream politicians’ attention, it was not banned. However, many of the carvings are currently lost as activists who had collected them faced increasing repression and had to distribute them among supporters. They are likely to be in the homes of workers and peasants today, but as far as is known, no library, archive ormuseum in Kenya has the collection – another reflection of the neo-colonial control over people’s culture. Settler and foreign artwork is easy to find in Kenya today, but sadly the same does not apply to Kenya’s artwork. The accompanying images reproduce some of the ones rescued from imperialist claws.

What thus emerged on the art and historical fronts was truly remarkable. At one level, the carvings demolished the ruling classes’ embargo on protest and resistance – here was the real history of Kenya which had been silenced since independence. At another level, they used a form where no words were written, no embargoes broken – yet history was there for all to see. It mattered not whether one had reading skills or not, whether one was fluent in English or not. The form and content were in perfect harmony, to give visual evidence of the heroic struggle. The neocolonial embargo on history, on information, on communications was totally broken. While historians could not do research or disseminate the results of their research to the people whose history they were working on, this group of artist-scholars created the history of the hidden aspects of Mau Mau. They highlighted the key vision of the movement which challenged the colonial and imperialist-induced social values. They explained their position on burning issues of the day and threw light on the historical approaches to resolving social contradictions.

Resistance Art

The neocolonial setup in Kenya in 1976 had ensured that people’s art and culture served only tourist markets, divorcing them from lives of working classes. The wood art of the Kamba nationality had been one of the victims of the attacks on people’s customs and cultures. It was gradually depoliticised by market forces, which became the new rulers under capitalism and imperialism. Tourists do not want politics, just items of what they consider ‘beauty’, and the Wakamba artists began producing wood carving of animals which satisfied the tourist and overseas markets. The needs of the Kenyan people remained ignored. Until, that is, the youthful group of the activist carvers broke the embargo imposed by the market economy. They pioneered a new art form with relevant content in their revolutionary wood carvings. They put politics in command once more in art.

For all their achievements, the artists remain almost unknown in Kenyan history today. They were Mule wa Musembi, Kitonyi wa Kyongo, Kitaka wa Mutua and Mutunga wa Musembi. The exhibition was curated by Sultan Somjee from the University of Nairobi.

Little was known in Kenya about the history of Mau Mau in 1976 as research and publication on it had been suppressed by the government. It is therefore interesting to see the carvings dig out key aspects of Mau Mau. These include their ideology, their strategies and tactics, their actions, development of technologies, record keeping and communications, leadership as well as their attitude to women, nationalities and their class perspective. The write-up accompanying the exhibition contained historical facts not commonly known except to Mau Mau activists. For example, a team of two or more Mau Mau activists would carry messages from the Mau Mau High Command in the heart of Nyandarua to different Mau Mau centres, and to its armies, or to the progressive workers and peasants throughout the country. The carving project brought such facts to the public. The text accompanying Carving No 1 (unfortunately not included here) records the tactics of Mau Mau in communication when confronted by enemy soldiers:10

Two couriers carrying orders from the Kenya Defence Council are caught in the enemy ambush. One courier rushes at the enemy so that the other may escape and deliver the orders. The dying fighter digs deep the soil and exhorts his companion to continue. The courier crosses many ridges and valleys across Kenya.

With works like these, Kenyan artists became trendsetters in resistance art

Biographies of cited Kenyan political activists

GENERAL BAIMUNGE (19??-1965) was a Mau Mau general, and deputy to Dedan Kimathi. He refused to leave the forest at independence in 1963, demanding that the government give free land, jobs and assistance to Mau Mau. He was killed on 26 January 1965 “at the hands of the Uhuru (independent) government” of Jomo Kenyatta.11

PIO GAMA PINTO (1927-1965) was a trade unionist, journalist and nationalist. He was an anticolonial activist in Goa (then under Portuguese rule) and Kenya and was active in the Mau Mau liberation movement. After independence in Kenya, he continued his anti-imperialist struggle and supported socialism. He was assassinated on 24 February 1965.12

JOSIAH MWANGI KARIUKI (1929-1975) was a Mau Mau detainee, later a Member of Parliament. “In later years he became a widely popular spokesman for the peasantry and the poor, claiming that ‘we do not want a Kenya of ten millionaires and ten million beggars’ … he was brutally murdered on 2 March 1975. When he was killed he was campaigning against corruption and actively opposing the political leadership … ‘there was no doubt whatever that high authorities in Kenya were responsible for his murder’”

MARTIN SHIKUKU (1963-2012) was a Kenyan Member of Parliament from 1963 to1988. “Seen as a radical, he early declared himself ‘President of the Poor’. He paid for his prolonged opposition with detention in October 1975. He was adopted by Amnesty International as a prisoner of conscience. He was released in December 1978.”14 “In KANU, Shikuku gained a reputation as an outspoken backbencher, critical of corruption and abuses of power, and a defender of parliamentary privileges.”15

JEAN MARIE SERONEY (1925-1982) was Deputy Speaker of the Kenyan Parliament in 1975, when his support of Shikuku’s declaration that “KANU has been killed” led to his detention; he was adopted by Amnesty International as a prisoner of conscience. He was released in December 1978.16

MAKHAN SINGH JABBAL (1913-1973) has previously been profiled in this journal.17 He was, according to Carol Sicherman, a “Pre-eminent trade union leader. Secretary of the Labour Trade Union of Kenya when he organised a two-month strike in Nairobi (1937). Interned in India for five years (1940-1945). In 1949, he founded the East African Trade Union Congress with Fred Kubai. He was arrested in 1950 and restricted until 1961. His attempt to enter the trade union movement [after his release] was banned by the new leaders (after independence) ‘suspicious of his socialist’ leanings. He spent his final years writing a twovolume history of the [trade union] movement.”18 While in India, 1939-47, he was a member of the Communist Party and edited its newspaper. His son Hindpal says:

“My father, Makhan Singh … shall always be remembered as the father of the labour movement in Kenya. And since the labour movement was closely interwoven with the political movement in the colonial period, my father was also a great nationalist. He was amongst the first ones to use the slogan ‘Uhuru sasa’, meaning ‘Freedom Now’, in his famous speech in April 1950, at Kaloleni Hall, just a few days before his arrest and long detention by the Colonial Government in remote parts of Kenya, for more than eleven years.”19

NGUGI WA THIONG’O is an award-winning, world-renowned Kenyan writer and academic who writes primarily in Gikuyu. His work includes novels, plays, short stories, and essays, ranging from literary and social criticism to children’s literature. He is the founder and editor of the Gikuyu-language journal Mutuiri. In 1977, Ngugi embarked upon a novel form of theatre in his native Kenya that sought to liberate the theatrical process from what he held to be “the general bourgeois education system”, by encouraging spontaneity and audience participation in the performances. His project sought to “demystify” the theatrical process, and to avoid the “process of alienation [that] produces a gallery of active stars and an undifferentiated mass of grateful admirers” which, according to Ngugi, encourages passivity in “ordinary people”. Although his landmark play, Ngaahika Ndeenda, co-written with Ngugi wa Mirii, was a commercial success, it was shut down by the authoritarian Kenyan regime six weeks after its opening. Ngugi wa Thiong’o was subsequently imprisoned for over a year. Adopted as an Amnesty International prisoner of conscience, he was released from prison, and fled Kenya.20 For further information see Carol Sicherman’s book. 21

KOIGI WA WAMWERE (1949-) is a Kenyan politician, human rights activist, journalist and writer. He became famous for opposing both the Jomo Kenyatta and Daniel arap Moi regimes, both of which sent him to detention.22

GEORGE ANYONA (1945-2003) was elected an MP in 1977, but later that year was detained without trial by then President Jomo Kenyatta. Although released in 1978 by President Daniel arap Moi, he was arrested again in 1982, along with his longtime friend and veteran politician Jaramogi Oginga Odinga The two were detained without trial for attempting to form a political party, the Kenya African Socialist Alliance (KASA), to challenge the ruling party KANU. Shortly after their arrest, KANU pushed through a constitutional amendment, making Kenya a de facto one-party state. Released from detention in 1984, Anyona made a political comeback in 1990 during the clamour for multiparty democracy in Kenya. However, he was then arrested with several others on a charge of sedition.

After a marathon trial, the defendants were jailed for seven years. It was later revealed by an assistant minister in the Office of the President, John Keen, that the allegations were nothing but government fabrications, and in 1992 the defendants were released on bail and then had theirsentences quashed.23

Notes and References

- C Sicherman, Ngugi wa Thiong’o: the making of a rebel: a source book in Kenyan literature and resistance, Hans Zell, Documentary Research in African Literature, London, 1990, pp 90-91.

- GSU = General Services Unit. “Prime Minister Jomo Kenyatta started to build up GSU as a counter-balance to the army. President Moi also became more dependent on the GSU, which eventually gained the reputation of being the military arm of the executive branch, an allegation that continues to this day. Some of the GSU’s more controversial activities occurred in the months prior to the 1992 and 1997 general elections when its personnel mobilised against prodemocracy advocates and other anti-government elements.” – Maxon and Ofcansky, qv, pp 82-83.

- S. Durrani and K Waweru, Kenya: Repression and Resistance: From Colony to Neo-Colony, 1948-1990 (forthcoming).

- The Kenya Workers’ Party later became the December Twelve Movement, later still, Mwakenya (Union of Patriots for the Liberation of Kenya, known in Swahili as Muunganowa Wazalendowa Kukomboa Kenya).

- Pambana is Kiswahili for “struggle”.

- L McCluskey, Foreword to On Fighting On: An anthology of poems from the Bread and Roses Poetry Award, Culture Matters, London, 2017.

- Mao Tse-tung, Talks at the Yenan Forum on Literature and Art (1942), in Selected Works, Vol IV, Lawrence & Wishart, 1956; online at https:// www.marxists.org/reference/archive/mao/selected-works/volume- 3/ mswv3_08.htm.

- InDependent Kenya was circulated in cyclostyled form in Kenya in 1981. In 1982 it was published in London by Zed Press and sponsored by the Journal of African Marxists “in solidarity with the authors”.

- S. Durrani, Progressive Librarianship: Perspectives from Kenya and Britain, 1979-2010, Vita Books, Nairobi, p 131. 7

- Publicity leaflet, History of Kenya, 1952-1958: A guide to the exhibition by Kenyan artists Mule wa Musembi, Kitonyi wa Kyongo, Kitaka wa Mutua and Mutunga wa Musembi, held at Cottage Crafts, Nairobi in 1976.

- Sicherman, op cit, p 105, quoting sources.

- See S Durrani, Pia Gama Pinto: Kenya’s Unsung Martyr 1927-1965, Vita Books, Kenya, 2018, reviewed by C Fernandes in CR90, Winter 2018- 2019, pp 23-26.

- Sicherman, op cit, pp 125-6, quoting sources.

- Ibid, p 178.

- RM Maxon and TP Ofcansky, Historical Dictionary of Kenya (African Historical Dictionaries, No 77), Scarecrow, Langham, MD, 2d edn, 2000, p 235.

- Sicherman, op cit, p 177.

- See S Durrani, ‘Reflections on the Revolutionary Legacy of Makhan Singh in Kenya’, Autumn 2014, pp 10-17.

- Sicherman, op cit, pp 178-9.

- S Durrani, Makhan Singh: A Revolutionary Kenyan Trade Unionist, Vita Books, Nairobi, 2015, p 15.

- See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ngũgĩ wa Thiong%27o.

- Sicherman, op cit.

- See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Koigi_wa_Wamwere.

- See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Anyona

Women in Struggle: Armed Mau Mau

women fighters marching into action.

Manufacture: Mau Mau inventors and

technicians in a gun factory in a cave

Women’s role is in the struggle: Protect

family, collect food and confront homeguards

Democracy: Decisions made in meetings while ready to confront enemy: Kenya Defence Council meeting.

War of independence: British fighter jets are powerless to stop resistance

Mau Mau activists continue their resistance while homeguards look for them in vain.

Colonial justice: Fearless fighter confronts

judge and armed homeguard: The trial of

Dedan Kimathi

Multi-nationality Mau Mau forces: Senior Chief Mukudi of Samia and Bunyala with Mau Mau fighters