Introduction

The history of Kenya is not complete without the history of trade unions, which made it clear that Kenya was a class-divided country — a fact that colonialism and imperialism wanted to hide by creating an impression of a race-divided country. The trade union movement, led by Makhan Singh, Bildad Kaggia, Fred Kubai and others, showed the clear division between the interests of the working class and those of the foreign corporations and white settlers under capitalism. The trade union movement showed that the interests of workers and peasants could only be safeguarded by an active struggle in the political as well as in the economic front. Focusing on only one of these was not likely to succeed in national or class fields. Thus, the trade union movement carried on its political struggle into the Mau Mau movement as well as in other aspects of national struggles while retaining the industrial struggles as its main front.

The Early Years

Resistance by working people of Kenya to European colonialism and imperialism had been continuous from the earliest days of their invasion of Kenya, first from Portugal, later from Britain. After the Berlin Conference of 1886, British colonialism became the main agent of capitalism and imperialism in Kenya. In the early years, resistance was led by almost every nationality in every part of the country.

It was the construction of the railways that can be seen as the development of a working class and working class consciousness in Kenya. Singh (1969, 2) explains the start of the capitalist system:

With the advent of British imperialist colonial rule, both the slave-system of the coast and the voluntary labour system of the free African tribal territories were replaced by a system of forced wage-labour. Under this system the slaves of the slave-owner and the free tribesmen all became forced labourers. They were first deprived of land and then compelled to work under horrible conditions for a meagre wage for a settler or another employer. Slave economy and free tribal subsistence-economy were both replaced by colonial capitalist economy. The system of forced labour came into existence. It met with resistance right from the beginning.

Working class consciousness and class struggle against capitalism and imperialism came with the construction of the railways. Among the earliest strikes was the one in 1900 which started in Mombasa and then spread along the railway line. The strike was by European sub-ordinate staff, Asian and African workers. Among early strikes were the following:

- 1902: 50 African police constable on strike in Mombasa.

- 1908: strike by African workers at a government farm in Mazeras and by railway workers.

- 1912: Strike by African boat workers in Mombasa.

- 1914: Indian railway and public works department workers on strike against Poll Tax. The strike lasted a week and ended with assurance that their demands would be considered, but three workers’ leaders were deported.

Early trade unions in 1914 included a number of Indian Trade Unions in Mombasa and Nairobi. Besides political organisations, there were some workers’ associations as well. These included Indian Civil Servants Association (1917), Railway Indian Staff Association, the Kenya African Civil Servants Association, the Railway African Staff Association. ‘Artisans and labourers were not allowed to join the staff or civil servants associations’, says Makhan Singh (1969, 40) as he continues: ‘It was thought that with their joining, the associations would become “trade unions”, which in case of necessity could back their demands with strikes’. The colonialists understood class contradictions perfectly!

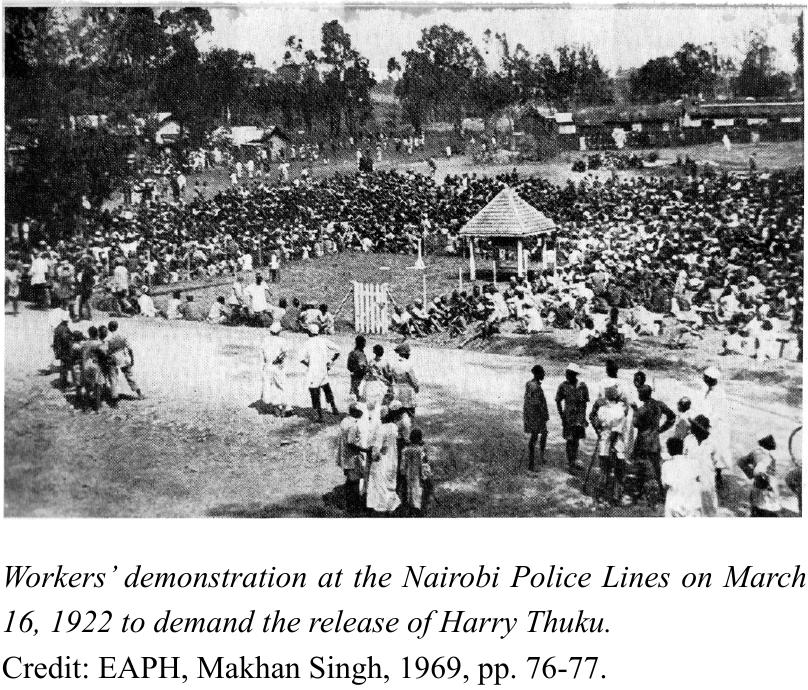

Workers’ activities kept increasing over the years, with a General Strike in 1922. The Government used the KAR (Kenya African Rifles) troops with armoured cars and machine guns in order to break the strike. The troops fired on the unarmed people at the demonstration for the release of Harry Thuku, leader of the East African Association, and 150 people were killed. Singh (1969, 16) sees the General Strike as an important milestone in the working class’ history of Kenya:

Thus, on that historic day the tree of Uhuru was watered by the blood of our martyrs. They were martyrs of Kenya’s national movement and trade union movement. The fight for Kenya’s independence and for workers’ rights began in great earnest with modern methods. And there took place the first General Strike of African workers in East African territories for political and economic demands.

A new chapter in the history of Kenya had begun.

During this period, African associations like East African Association — later changed to Kikuyu Central Association — and the Kavirondo Taxpayers Welfare Association ‘acted as general workers’ unions in addition to acting as political and social organisations’ (Singh, 1969, 40). These regional associations, rather than national ones, were formed as the Government refused to allow national bodies to exist.

1931 was an important year in the trade union history of Kenya. A mass meeting of about 1,000 artisans, masons, workmen and labourers was held in Mombasa in February in response to falling wages, lengthening working hours and deteriorating conditions of employment’ (Singh, 1969, 41). The meeting decided to form the Trade Union Committee of Mombasa. Among its demands was an eight-hour workday. However, the Committee functioned only for a few months. An interesting development was a successful strike by workers of the Kenya and Uganda Railways and Harbours, organised without a trade union. The strikers ‘had used canteens, clubs and occasions of ngomas (dances) for holding meetings in connection with the strike. This method of using social occasions for discussing workers’ grievances and taking decisions was at the time prevalent throughout Kenya and other East African territories’, says Makhan Singh (1969, 46).

Another attempt to form a trade union was made in Nairobi in the same year (1931) when the Workers’ Protective Society of Kenya was formed. However, an important development was the decision by the newly formed Indian Trade Union that the union would be open to non-railway workers, creating the possibility of a broader organisation. The union was formed at a mass meeting of workers in December 1934 in Nairobi. The union changed its name later the same year to Kenya Indian Labour Trade Union. Singh (1969, 47) highlights one of the problems facing the trade union movement at that time, but it has relevance today as well:

The basic difficulty was the usual one. There was no team of workers who, after having been elected officials of the union, were prepared to devote their time regularly and fearlessly to making the union function in a spirit of co-operation, unity, sacrifice and service.

Singh explains some of the difficulties facing all the unions:

The reasons for the lack of such a team were not hard to find. The trade union functionaries from the very beginning had to face the general hostility of employers and the colonial rulers. The threat of victimisation by employers and/or deportation by the government was always there. Moreover, there was no trade union legislation. The nature of the existing labour legislation was such that there could only be discouragement for the formation of trade unions. The migratory character of workers made the continuity of a union nearly impossible. Industry was undeveloped: there was none worth the name except the railway. This made the employment of a worker generally short-lived, so that he was compelled to go from job to job, workshop to workshop, town to town. All these factors equally affected the trade unionists. So, it was no wonder that the Kenya Indian Labour Trade Union was in the same quandary as some of its predecessors.

A strike by African fishermen at Kisumu took place in February 1935. ‘The solidarity and the united struggle of the fishermen compelled the employers to increase their remunerations’ (Singh, 1969, 47-48). Their achievement had lessons for the Kenya Indian Labour Trade Union, as Singh explains:

In view of the common interests of workers in Kenya, there was no solution to the difficulties of the Kenya Indian Labour Trade Union as long as the Indian and African workers pursued their aims separately. The solution lay in it becoming a non-racial trade union to harness and mobilise the energies and fighting spirit of the African, Indian and other workers of Kenya through a united trade union organisation. And adoption of this policy was soon to bring the incipient trade union movement out of its organisational and other difficulties.

So ends Phase One of the development of trade unions in Kenya.

Kenya Indian Labour TU becomes Labour Trade Union of Kenya (1935)

The change of name and the scope of the Kenya Indian Labour Trade Union helped to resolve some of the problems facing the union. However, an important hurdle remained, the one mentioned by Makhan Singh above — a ‘lack of workers who were prepared to devote their time regularly and fearlessly to making the union function in a spirit of co-operation, unity, sacrifice and service’. The railway artisans then asked Makhan Singh to help the union. He accepted and worked without any remuneration. From that time, the union got new life under the leadership of Makhan Singh. In April 1935, the union was renamed Labour Trade Union of Kenya; its membership was now open to all workers, ‘irrespective of race, race, religion, caste, creed, colour or tribe’. The union ‘was the only body in East Africa that could struggle for the demands of workers’, as stated by the union communique. Union membership reached 480 by June 1935, half from railways. The first aim of the union was to ‘organise the workers of Kenya on a class basis’. (Singh, 1969, 51).

While the union was a general workers’ body, it also aimed to be a base of organising workers according to industries and uniting all the unions in a central organisation of trade unions. Among its early activities was the effort to address the problem of long working hours. It was decided at a mass meeting of workers in August 1935 to struggle for an eight-hour workday. In the meantime, the union helped the formation of the Print Workers Union with Makhan Singh as Secretary. The Second AGM of the LTUK fixed October 1, 1936 as the date for the implementation of the eight-hour workday. The principled stand of the union, together with the steadfast support of members, forced employers to accede to the demand. The success showed that trade unions could be a powerful tool for worker rights. Makhan Singh (1969, 54-55) reflects on the campaign:

…with the increasing tempo of the campaign and seeing the increasing unity and strength of the workers, who were ready to go on strike at the call of the union, all employers agreed to the demand … The campaign was completely successful. This was the first time that African workers saw the union in action …The effect of the success was felt all over Kenya, and in Uganda and Tanganyika, too. The membership of the union went up to more than 1,000.

The months that followed saw a number of strikes all over the country:

- October-November 1936: three strikes took place, two at the works of two building contractors: both were successful. The third one was in the Public Works Department, which was also successful.

- October 1936: Strike by 800 African workers employed in a sugar estate near Nairobi.

- December 1936: Another strike of the lake fishermen in Asembo Bay. Here also, the unity and solidarity of the fishermen were so strong that the employers had to agree to workers’ demands.

Following the success of the campaign for an eight- hour workday, the union decided at a mass meeting of workers on December 20, 1936 to demand wage increases of 25 per cent from April 1, 1937 from Indian employers. The demand became popular in Kenya as well as in Uganda and Tanganyika. The union decided to change its name to Labour Trade Union of East Africa, given the support it had in all three countries. A strike in support for the wage increase was called on April 1, 1937. Makhan Singh (1969,60) explains the campaign:

It was a complete strike. A strike committee was formed. Picketing was organised. A free kitchen was started, where strikers and unemployed could have their food.

By April 11, all employers accepted the union’s demands. It next turned its attention to European builders. After the longest strike in Kenya’s history lasting 62 days, the European employers agreed to wage increases of between 15 and 22 per cent, an eight-hour workday and reinstatement of all strikers.

Facing increasing militancy from workers, the Government introduced the Trade Unions Ordinance in 1937 which provided ‘legal protection for registered unions and for peaceful picketing during strikes’. It was also meant to control militancy in unions. The Labour Trade Union of East Africa (LTUEA) was registered under the new legislation in September 1937. ‘Trade Unionism in Kenya had come to stay’, says Makhan Singh (1969, 65).

An indication of the future direction of trade unionism in linking economic with political demands is given by the resolution of the third annual conference of LTUEA in July 1939. The conference was attended by ‘thousands of African and Asian workers’ (Singh, 1969, 80) indicating the growing strength of the trade union movement among African and Asian workers. The Conference received messages of greetings from the British Trade Union Congress, the Colonial Information Bulletin, London and the Chemical Workers Union in Johannesburg. These international links were most likely established by Makhan Singh. The Conference passed the following resolution (Singh, 1969, 82) indicating the unionists’ awareness and interest in international working class and political struggles:

The conference expressed “its deepest sympathy and heartiest solidarity with the people of India. China, Palestine and Abyssinia (Ethiopia) in their struggle for freedom and human rights, and also with the workers of West Indies and West Africa in their struggle for better conditions.”

The Conference then set out its demands for the working class in East Africa:

(a) Freedom of speech;

(b) Freedom of meeting and procession;

(c) Freedom of press;

(d) Freedom of movement;

(e) Freedom of organisation.

Singh (1969, 62) sets out the importance of the decisions of the LTUEA Conference:

The real significance (of the decisions and resolutions) lay in the fact that they had resulted from the joint deliberations of African and Asian workers for the first time in East Africa. The workers’ unity demonstrated at the conference had an immediate effect upon the African workers’ struggle, especially in the railways and amongst other workers in Mombasa. There the chain of struggles started by the African railway apprentices’ strike was continuing and was soon to develop into the Mombasa African Workers’ General Strike of 1939 … Trade unionism in Kenya was forging ahead.

These experiences of strikes and worker struggles influenced events over many years.

Mombasa General Strike, 1939

Workers in Mombasa got more militant and started organising strikes in a number of industries. ‘In July and August 1939, there was a series of African workers’ strikes in Mombasa, popularly known as the Mombasa African Workers’ Strike of 1939’, says Singh (1969, 83). The strike led to the grievances of workers being openly aired with some progress achieved in addressing them, for example, housing and housing allowance began to be paid, some wage increases were achieved and the need for ‘organisation of trade unions began to be felt … the trade union movement in Kenya was now moving forward at great speed (Singh, 1969,94).

The General Strike of 1950

Union militancy continued until May 1950 when Fred Kubai and Makhan Singh were arrested on a charge of being officials of ‘an unregistered trade union’, the EATUC’. The records of the Union were removed by the CID and their offices were closed (pp. 268-9 ). Members of the Central Council of EATUC discussed the arrests and concluded that the Government’s action in arresting EATUC leaders was ‘a serious attack on Kenya’s trade union movement and that it must be resisted’ (p.270). The meeting decided to call a general strike starting on May 16,1950 for the following economic and political demands:

- Release of Makhan Singh, Fred Kubai and Chege Kibachia.

- A minimum wage of Sh100/-.

- Abolition of the municipal by-laws regarding taxi drivers.

- We do not want workers arrested at night in their houses.

- We want freedom for all workers and freedom of East African territories.

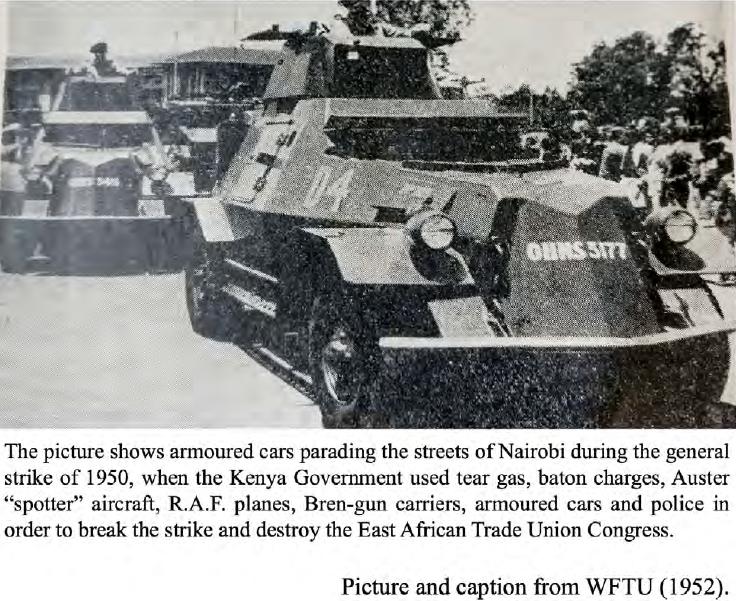

Frightened by the planned strikes, the Government rushed through new legislation making strikes in essential services illegal, hoping to control the strike. In addition, it arrested Chege Kiburu, the Acting President of EATUC and issued a warrant of arrest for Mwangi Macharia, the acting General Secretary of the union. These actions had no effect on the union and workers. By the following morning, ‘the general strike was in full force in Nairobi, Nakuru, Mombasa and some other parts of Kenya’ (p. 272). The strike demonstrated the solidarity with workers from peasants and other working people, as Singh (1969, p. 272) shows:

The sympathy and solidarity of the people was so great that food (maize, potatoes, sweet potatoes and sugar cane) began to be donated in the areas adjoining Nairobi and other towns for the strikers and their families. The donations continued on a very large scale throughout the strike.

It was this solidarity that was the strength of workers, which enabled them to take strike action. The workers also created symbols of the strike to strengthen their resolve to continue the strike. Again, Singh, (1969, 272) explains:

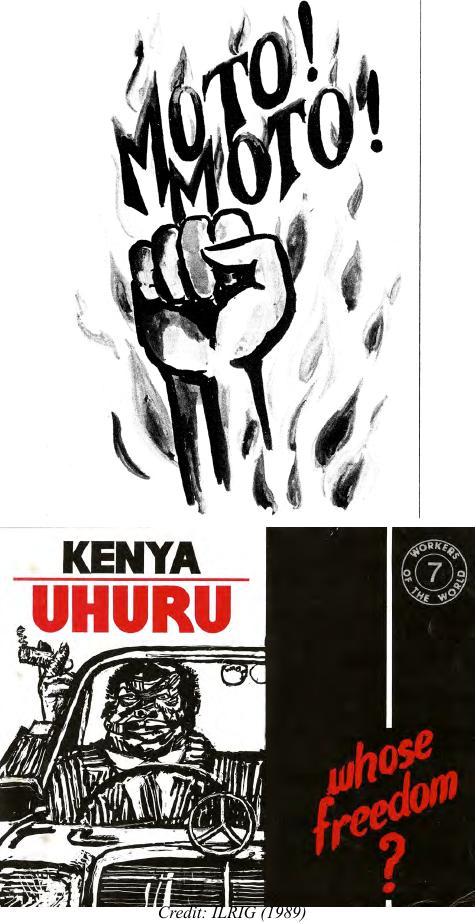

The same day (17 May, 1950) a bonfire was lit on the left bank of Nairobi River in the valley of Pumwani and Shauri Moyo, Nairobi. The fire was fed by trunks and branches of trees in the area as well as from nearby areas. The fire expressed the fighting spirit of the strikers as well as of the people of Kenya for freedom and independence. “MOTO MOTO” became the slogan everywhere. The fire was also the sign of the continuation of the strike. Whether the services were “essential” or “non-essential” the attitude of the strikers was of defiance of the colonial authority.

The significance of the fire (‘Moto-Moto’) was that ‘the fire should be kept burning as long as the strike continued’ (quoting Assistant Superintendent Henderson, E.A. Standard, 23-05,1950, as quoted in Singh (1969, 276).

The strikes continued nationwide. By May 18, 1950 there were general strikes in Kisumu, Kakamega, Kisii, Mombasa, Thika, Nyeri and Nanyuki, among other places. The strikes spread further over the following few days: 750 African railway employees in the central workshops, 1,000 workers, including from Bata Shoe Factory, 60 African employees at Eastleigh airport, and workers at ‘various war department establishments’. These strikes were in addition to those taking place through the country in which ‘thousands were participating since the beginning of the general strike’ (p.275). The authorities could do nothing to stop the strikes and so began intimidating workers with armed forces and arresting workers. But this did not stop the strikes.

Within 9 days, by May 24, more than a 100,000 workers had taken strike action all over the country. The union decided to end the strike on May 25 as ‘sufficient protest and demonstration had taken place’ but decided to carry on the struggle by all possible means. It was ‘a great general strike in the history of the Kenya trade union movement as well as the national movement’, says Singh (p. 277). However, not all the strikes ended. The one by the Typographical Union of Kenya went on for 28 days and ended on June 12, 1950 with an agreement which gave the workers a 10 per cent increase in salaries, regular annual increments, 14-day annual leave and the same amount of sick leave, termination notice of one month, equal pay for equal work, among other improvements in working conditions. Similarly, the workers of the Tailors and Garments Workers Union saw increased wages as a result of their strikes.

As for the general strike, it led to an increase in the minimum wage in all main towns from August 1, 1950. Singh (287) sums up the achievement of the workers in strikes and other actions:

The two agreements and the increased minimum wages were a great victory for the trade union movement. They reflected the tremendous unity, awakening and upsurge of workers and other peoples of Kenya, generated by the trade unions and the East African Trade Unions Congress and by the general strike, which had also greatly advanced the freedom struggle in Kenya and other East African territories.

The key point to note is that the struggle for workers and their trade unions were not only for increased wages and better working conditions. They realised that their economic interests could be safeguarded and advanced only if the struggle against capitalism, colonialism and imperialism were waged simultaneously. It is this linkage that was to play a crucial part in Kenya’s war of independence and in Mau Mau.

Mau Mau and Trade Unions

An important aspect of people’s resistance that imperialism seeks to hide is the role of trade unions in the fight for the liberation of workers from capitalist exploitation. What is often ignored or forgotten is the key role that the trade unions played in the war of independence. Working class activism helped build anti-imperialist solidarity and gave an ideological framework that eventually became the economic and political demands of independence. The working class came from all parts of the country and from all nationalities, from all genders and their participation in the struggles made this a national struggle. It suited colonialism and imperialism, as part of the divide and rule policy, to ignore that the working class had anything to do with the war of independence. And it is no surprise that Kenyan comprador governments after independence, reflecting imperialist interests, have similarly ignored the role of trade unions. Trade unions were early targets of the Kenyatta government. Indeed, the concept of class is all but absent from imperialist interpretation of colonial history. This then leads to a misrepresentation of the aims and methods used by the liberation forces.

The trade union involvement in the struggle for independence and in Mau Mau has been covered by a number of titles listed in the References & Bibliography section.

References

– Durrani, Shiraz (2018): Kenya’s War of Independence: Mau Mau and its Legacy of Resistance to Colonialism and Imperialism, 1948-1990. Nairobi: Vita Books.

– Durrani, Shiraz (2018): Mau Mau the Revolutionary, Anti-Imperialist Force from Kenya: 1948-1963. Kenya Resists Series, 1. Nairobi: Vita Books.

– Durrani, Shiraz (2018): Trade Unions in Kenya’s War of Independence. Kenya Resists Series, 2. Nairobi: Vita Books.

– ILRIG (The International Labour Research and Information Group. 1989): Kenya Uhuru, Whose Freedom? Salt River, South Africa: ILRIG. – Singh, Makhan (1969): History of Kenya’s Trade Union Movement to 1952. Nairobi: East African Publishing House.