Introduction

Kenya was among the leaders in Africa in its anticolonial struggle waged by workers and peasants under Mau Mau. This resistance achieved independence in 1963 and broke the back of British colonialism. But capitalism and imperialism were not to be defeated so easily. Using well-developed tactics of looting, creating disunity based on class, race, religion, gender and other real or created divisions, the agents of capitalism and imperialism installed a capitalist-friendly class as the new elite ruler.

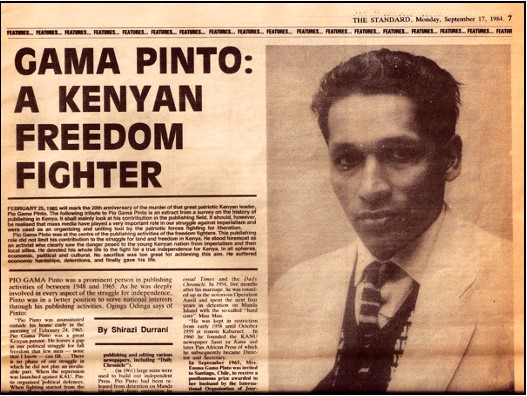

The new rulers were then handed colonial era laws and institutions backed by local and foreign armed forces to ensure their survival in power. Thus, capitalism soon saw off the challenge from democratic and socialist forces. In came Jomo Kenyatta and Daniel arap Moi. Oginga Odinga, Bildad Kaggia, Fred Kubai, Makhan Singh, the Mau Mau and trade union activists were eliminated from political life. Pio Gama Pinto was assassinated in 1965. Massacres, murders, disappearances, and exiling were the order of the day. The Kenya People’s Union was suppressed in 1969. This saw the end of all peaceful and democratic attempts to oppose capitalism and KANU-B.

And so began the second phase of Kenya’s resistance. Several underground organisations began springing up, the most prominent being the December Twelve Movement (DTM) which later became Mwakenya (MK). Their policies and ideological struggles were a continuation of the struggles of earlier periods. History cannot be compartmentalised into neat blocks as events overflow from one generation to the next, from one decade and from one century to the next. A look at the achievements and challenges of the December Twelve Movement (DTM) can help to set the period in a better perspective. The history and record of Mwakenya, which succeeded DTM around 1985, remains outside the scope of this article.

Kenya was not the only country attacked by imperialism, which ensured that attempts to liberate Africa failed. Imperialism created Africa in its own image. First, it split the continent into countries to suit its own purpose to loot and exploit. Within each country, it divided people who had previously lived relatively peaceful lives into antagonist classes, religions, regions, races, and many other social divisions — real or created by imperialism. A situation similar to what Kenya faced obtained in almost all countries of Africa, of course with local particularities. Any solution found in one country thus has relevance to many others.

Imperialism ensured that Kwame Nkrumah, Patrice Lumumba, Thomas Sankara, Muammar Gaddafi and many others did not succeed in liberating their countries and Africa from the clutches of capitalism and imperialism. It ensured that the Kenya People’s Union failed.

Any open political parties and movements could not survive. In this situation, underground political movements seemed the only way to challenge imperialism. That is what the December Twelve Movement in Kenya did. The work of DTM has significance far beyond Kenya’s borders, and far beyond its own timeframe.

December Twelve Movement and Its Ideology

The struggle for liberation from capitalism and imperialism in Kenya took a new turn with independence in 1963. Gone, at least from the surface, were the colonialists and the White settlers who had dominated the political and economic policies before. In came the ‘new’ capitalists under Kenyatta and KANU-B (Kenya African National Union) with the same agenda as the colonialists.

People resisted and opposed the capture of the country by the new ruling elite which had the support of imperialist Britain and USA.. The new capitalists captured not only state power and national resources; they captured the history of resistance, too. Included in this suppression was the history of December Twelve Movement (DTM), which has either been removed from the history books or its significance has been dismissed as the ‘shadowy December 12th Movement’(Hornsby, 414), while Maxon and Ofcansky (2000, 52) describe it as a ‘dissident opposition organisation’ without any other details. There have been few attempts to examine its documents or to assess its record and achievement and so the movement is not known as widely as it should be.

Another reason that DTM has remained outside the public domain is the prominence given to Mwakenya, its successor, as it became national news once the Moi government decided to use its existence as an excuse to detain, jail and torture all those opposed to his dictatorship. The limelight that Mwakenya found itself in pushed DTM further into the shadows. While Mwakenya was a successor movement of DTM, there were many differences between the two organisations, which have also not been investigated.

At the same time, as DTM was an underground movement, not many of its documents were collected and preserved by public libraries and archives, partly out of political expediency, given the prevailing atmosphere of fear created by Moi. Activists at the time could not preserve many of the movement’s documents, as being found with one was dangerous under the Moi government. The fact that many of its activists have chosen to remain silent about the organisation, even now, has pushed the story of DTM even further into the shadows of history.

Kinyatti (2019, 332) traces the origin of DTM to the Workers Party of Kenya (WPK), which he says was founded in December 1974:

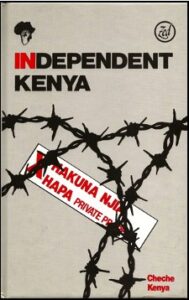

The publication of Cheche Kenya (1981) and Pambana (1982) prepared the ideological path for the transformation of WPK into the December Twelve Movement (DTM) in May of 1982

If the above is correct, then the question about its activities in the period 1974 to 1981 remains unanswered. Yet, this was the period when many activities by DTM were taking place, particularly in the cultural, educational and academic fields as well as in organising underground cells. These imply that the ‘ideological path’ was well set by the early 1970s. In addition, many pamphlets were published but are difficult to acquire now, as they were produced and distributed underground.

The absence of these pamphlets is a loss of part of the history of resistance in Kenya. Ong’wen, in a forthcoming memoir, gives some background on DTM’s pamphleteering work and mentions one in particular:

Anonymous leaflets had been produced and distributed by the Movement [December Twelve Movement] on previous occasions. For example, since April 1975, the Movement had produced a newsletter titled Mwanguzi but its authorship was attributed to Kamati ya Ukombozi wa Kenya (Committee for the Liberation of Kenya). A committee in anyone’s mind would denote a handful of people. So, the State was not as much bothered. But a movement would be a completely different animal and the earlier it was tamed the safer the regime would feel. On March 2, 1980, to coincide with the fifth anniversary of the heinous assassination of JM [Kariuki], the Movement produced and circulated a leaflet titled, ‘JM Solidarity: Don’t Be Fooled, Reject These Nyayos.’ The onepager observed that Jomo Kenyatta was widely hated because his regime deprived the Kenyan people of their rights while administering to predatory appetites of a minority of locals and foreign imperialism.

Reflecting on the oppressive political situation at the time, Wachira (2019, Minute 47) sees the need for a core group of people who were ‘dedicated, selfless, progressive, underground, anonymous, not blowing their own horn, completely dedicated to people’. DTM provided such a core.

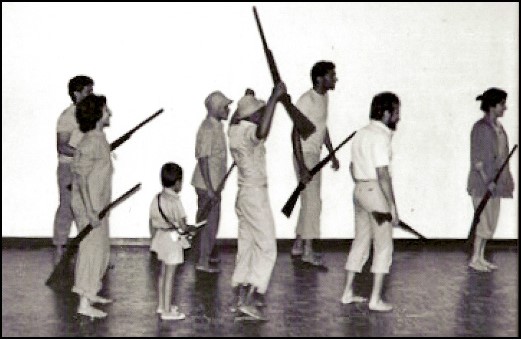

Kenyan politics is often seen from the perspective of the activities of registered political parties. In this case, it is the formation of the Kenya People Union (KPU) in 1966 and its banning in 1969 that is generally regarded as the active period of resistance to capitalism and resistance to KANU and Kenyatta’s regime. Forgotten in this rush to compartmentalise history is the growth and activities of underground movements. Wachira (2019) mentions activities that took place in the early 1970s that were to lead to the publication of Cheche Kenya’s InDependent Kenya in 1981. Wachira (Minute 47) sees the events of this period as being a bridge to the multi-party movement in the 1990s, saying that the previous generations had built foundations on which others stood and built up later. Open political expression of alternative views was not possible, he says, and the underground was the only alternative. In order to be effective, however, the underground needed to have over-ground activities so as to reach people whenever conditions allowed. Such activities included writing and distributing pamphlets, cultural activities such as plays, travelling theatre, village theatre, and journalists’ press pieces. There was, he says, a continuous, seamless set of activities that reflected the underlying clamour for change. It was in these circumstances that the underground brought out Cheche Kenya’s InDependent Kenya in 1981 — which was published by Zed Press in London in 1982. Cheche Kenya went through various name changes before settling for December Twelve Movement.

DTM was anti-imperialist and anti-capitalism, as is clear from its publications. Its vision for Kenya was a socialist one. In addition, it took a clear class position in the class struggle in Kenya, as Ong’wen says in his forthcoming memoir: “Class sentiment and class organisation was at the core of resistance spearheaded by the DTM”.

How was DTM Organised

DTM was organised into cells or uniti as Mazrui and Mutunga (2014) call it:

Our “uniti” had other problems, of course, including liberalism and indiscipline among some members at particular moments. These were addressed openly with the kind of criticism that they deserved. In a way this was part of the process of maturing as a political organization … He [referring to a member of the cell] would easily lie (to himself and others) or distort the truth to maintain the cult of personality, which he was so eager to construct around himself. As a result, a reasoned, healthy and self-reflective critical discourse of our own beliefs, ideas and conclusions was virtually impossible under these circumstances. And whenever uncomfortable questions were raised, there was always the undemocratic resort to claims of “orders from the ‘higher’ uniti’” as a way of evading open discussion and accountability. Some of us had, in fact, planned on confronting these internal tendencies of dictatorship and nonaccountability more aggressively. Sadly, thanks to [the member’s] adventurism and hoarding, we were arrested before we could do so.

This shows a number of important facts about DTM. First, that the tradition of a ‘healthy, reasoned and self-reflective critical discourse of our own beliefs, ideas and conclusions’ was the norm in the work of cells. Second, DTM members were aware of the danger from liberalism and the need to challenge such tendencies There was another instance in another cell where members challenged their leader over his liberalism and being paralysed with fear in the face of Moi’s repression and, in fact, suspended him from leadership. His was, perhaps, a unique case. So fearful had he become that as the leader of the cell, he could not even look after or dispose of the DTM rubber stamp. He then passed the stamp on to a cell member to dispose of it. This she did expertly without fear or panic. It thus became clear to cell members that leaders do not always lead. Following the leader’s suspension, cell members approached another member at a ‘higher’ level in the organisation several times for guidance and support. Unfortunately, he did not respond to the pleas from the cell. This particular cell was a strong one with a large network of sub-cells going deep into the countryside and among urban workers and in working class residences in Nairobi. It could have replaced the leadership, which was jailed or exiled, but it lacked the contact details of other cells. The opportunity to revive DTM was thus lost, further weakening it just at the time it needed to be strong in the face of Moi’s intensifying repression.

Yet, such incidents indicate that DTM was a mature political movement where members engaged in criticism and self-criticism, thereby strengthening the organisation. Had DTM survived, such experiences would have steeled it in its would have steeled it in its fight with with the ruling class. As it was, the experience of DTM members in exile, with the support of others, was to lead to the formation of Umoja and the revival of Mwakenya. Many former DTM members are active in the struggle in different ways in Kenya and elsewhere.

Mazrui and Mutunga (2014) further highlight another aspect of the work of the uniti:

During our years in the organization, all intellectual/scholarly projects of individual members of the organization — including Maina [wa Kinyatti]’s Thunder from the Mountains and Ngugi [wa Thing’o]’s Detained — were essentially projects of the movement. The manuscripts circulated amongst, and received comments from, all of us. Those publications captured the collective intellect of the movement as well as the lasting revolutionary spirit of the time.

This highlights another way in which history has been distorted: the collective work by a political group, in this case the December Twelve Movement, has come to be seen as the work of individuals, thereby de-emphasising and de-politicising the collective political effort. Under capitalism, the individual is supreme, and the collective is relegated to the margins. The efforts of DTM to place emphasis on the collective is defeated by capitalist perspectives to make the individual reign supreme. It has not helped when individuals then also remain silent about the collective effort that went into such ‘individual’ works.

DTM was not a mass party like KANU, not anyone could join it just by paying membership fees. Members had to demonstrate ideological clarity in study sessions and then show in their practice that they were ready to join the organisation in its struggle against capitalism and imperialism. Ong’wen provides an insider’s perspective on the organisational aspect of DTM:

In May 1982, the first issue of Pambana: Organ of the December Twelve Movement, was published. This was as a result of intense discussions in the cells and study circles. G coordinated our study circle. I was not yet a full member, only a candidate of the Movement but belonged to one of the, presumably, many study circles. Study circles were focused discussion groups through which potential cadres were identified and apprenticed before eventually being introduced to the Movement as members of a cell

The other way to restore the history of DTM is by looking at its publications. While many pamphlets and other publications have been lost, some key documents have survived and are examined in the section that follows

InDependent Kenya (1981)

InDependent Kenya was an important departure in the history of Kenya. The Kenya People’s Union (KPU) had come out with its Manifesto and Wananchi Declaration but it was prevented from issuing detailed analysis on Kenya by the incessant attacks from the government. DTM, being underground, had no such distractions from the government and so could focus on clarifying its ideological position, in organising study and political cells, and in producing analyses of the situation in Kenya with its recommendation for change. InDependent Kenya, distributed in Kenya in 1981, played this part admirably. The authors explain the background of the book:

This study has been produced by a discussion group, which has met over a lengthy period to investigate and debate the issues of national interest (xii)

It was thus a collective work of the DTM and not the product of an individual working on their own. They then show ‘where we are now, what has become of our country, and why’, explaining the ‘situation in its proper perspective’:

For we have not been brought to our present impasse solely by this or that individual. The system, which dominates and oppresses us, is larger than the personalities who serve it. What we must actively oppose is the system, not simply any particular individual or even the entire ruling clique. In the future, individuals will come and go, but the system will remain the same, or worse, unless we can look beyond personalities to the underlying realities, which have denied us meaningful independence. Future politics must again deal with these realities — with issues — not merely with personalities. By recognising the issues at stake, we will gradually be able to regain the singleness of purpose and the power we possessed when we took up arms against the system of colonialism, not merely against this or that colonial governor. That system has been perpetuated in ‘independent’ Kenya in a different guise. That system remains the enemy. We can only go forward if we are clear on this fact and prepared for sacrifice and united resistance.

DTM thus clarified perhaps one of the most misunderstood realities in Kenya after independence: it is the system that needs to be changed, not merely the individuals who front it. Mwakenya was later to return to this theme when it stated, Hata Bila Moi, Umoi Tunapinga!’ (Mwakenya, 1992). That clarity is needed today as much as it was in 1981. The system it wanted to replace capitalism with was socialism, although it is difficult to understand why it did not mention this goal clearly in its publications.

It should be noted that the original InDependent Kenya was a cyclostyled document that circulated among members of DTM, its supporters and sympathisers. Behind the production of the book were not just the writers, but teams of dedicated activists who typed, duplicated, bound and distributed the document. Their presence has again been deleted from the pages of Kenya’s history. The publication of the document as a book by Zed Press in London in 1982 indicates yet another aspect of DTM: its links with progressive people overseas and its ability to broadcast its message far and wide. The book, which reached Kenyans all over the world, ran to 119 pages and is divided into five chapters:

- Birth of Our Power: Should we Forget the Past?

- KANU and Kenyatta: Independence for Sale

- Looters, Bankrupts and the Begging Bowl

- The Culture of Dependency: Hakuna Njia Hapa! [There is no way here]

- Conclusion: Twelekeeni [Let’s go!]

This is followed by nine (9) appendices headed: A Sampling of How the System Works, providing case studies to show the exploitative system at work. The conclusion sums up:

We have demonstrated in the foregoing chapters that ‘independence’ is a hoax in Kenya. For independence to be more than a word, the colonized must take charge of their own affairs and obliterate colonial social and economic forms, creating fresh ones in all spheres. But in Kenya, the entire colonial system was passed on virtually intact, and has been perpetuated in a practically unchanged form over the last two decades. Instead of British governors and their PCs [Provincial Commissioners], we now have Kenyan governors and their PCs, using the same, or even more repressive, laws and institutions to subdue our people’s expectations. Kenya’s rulers have, in fact, surpassed the colonialists in their determination to eliminate popular participation and association and to ensure docility.

The book, its content, its appearance on the Kenya scene in a dramatic fashion during a period of increasing repression and increased awareness of the damage that capitalism was doing to the lives of people, were indeed ground-breaking. The blurb on the book cover explains the content:

InDependent Kenya is a devastating expose of Kenya during the 20 years since Independence. In vigorous language and with lots of concrete examples, the authors tell the real story of Kenya today — the extent of corruption, the enrichment of certain individuals, the suppression of all opposition. They also analyse the country’s distorted economy, polarised class structure, and cultural dependency on the West. The book ends with an outline of the various political possibilities for the future, the authors arguing that the struggle for scientific socialism, while inevitable if the Kenyan people are to free themselves from poverty and repression, can only result from a lengthy and difficult period of political organization and struggle.

It explains the authorship of the book thus:

The authors are a group of Kenyans from various parts of the country. They have had to remain anonymous because they are still living there. The text had already circulated quite extensively in mimeographed form before political activity became almost impossible with the brutal repression that followed the air force uprising in late 1982.

This book remains an important contribution to Kenya and its resistance archives.

Pambana No. 1 (May 1982) — This is War, Class War

Pambana, the underground newspaper of DTM, was circulated widely in the country. Ong’wen gives the background to the publication in a forthcoming memoir:

During the discourse, it was noted that even with independence in 1963 the story did not change as far as ownership, focus and content of the mainstream press in Kenya was concerned … A need was thus felt for a consistent and regular communication and propaganda organ to expose the duplicity of Kenya’s flag independence and articulate the people’s aspirations and alternative worldview. Prior to the launch of Pambana, the movement developed a course content on “Leafleting and Pamphleteering.” The DTM was not under any illusion that the neo-colonial regime would let it run a newspaper or operate a radio station that would present the alternative. Even in the most unlikely event that the regime became so charitable as to allow it, the Movement did not have the wherewithal to establish it. What made the leaflet and pamphlet the preferred media to a newspaper or radio was that it was within the financial means of the Movement, which was solely raised from members’ contributions

Wachira (2019) says Pambana was distributed ‘in all big cities, in the highlands and countryside’. The first issue of Pambana came out in May 1982 and was in Kiswahili and English. Under the heading, ‘Our Stand’, it proclaimed Huu si Uhuru; Huu ni ukoloni mambo-leo — This is not independence; this is neo-colonialism. It goes on to explain that Kenya had become a victim of neo-colonialism and that its revolution ‘has been arrested and derailed’:

KANU and its government have disorganized all spheres of economic production, have scattered all communal efforts at organization, have sowed unprincipled discord and enmity among our peoples, and have looted unspeakable sums of money and national wealth. They have finally given our entire country over to US imperialism to use as a political and military base. All these crimes have been wrought in the name of “progress and prosperity” and … smatterings of “love, peace and unity”. This is NOT independence. This is neo-colonialism in its worst form. Kenyans have been massively betrayed. The revolution we launched with blood has been arrested and derailed.

The Editorial — reproduced in this issue of TKS — declared: ‘Our people want change, revolutionary change’ and looked at the role of revolutionary newspapers in ‘awakening, mobilising and unifying’ people’ quoting Lenin, ‘A Spark Can Light A Prairie Fire’.

Pambana carried national news showing the repression from the Moi government and people’s resistance to it. This included an article entitled, ‘Criminal Government Scandals and Cover-ups’ which summarised ‘various documents and information’ acquired by Pambana’. Included here is an item, ‘The President himself received cash payments of some six million from the Bank of Baroda to facilitate cover-ups and currency smuggling, and quash investigations’. Another item records: ‘The new crop of foreign banks in Nairobi are really conduits of currency smuggling and banking abroad for multinationals and big officials’. Another important section was entitled, ‘Land Battles’, which reported on events in ‘Gatundu [which was] the scene of a major confrontation between landless people and landed thieves … The farm was owned by a wife of Kenyatta … Kenyatta’s nephew, a government minister … joined hands in organising this major effort in robbery.

Pambana showed that DTM was aware that the struggle in Kenya could not be fully successful without the victory of similar movements around the world. It thus carried a section entitled, ‘International Struggles’ which included articles on the People’s War in Central America.

Pambana concluded:

December Twelve, 1963 was the day most Kenyan masses united with the hope of a national reality, a true independence. Unknown to them this was not to be. It signifies to us a betrayal and the basis of a new, higher unity and a revolutionary rebirth

Pambana recognised the part played by Cheche Kenya (InDependent Kenya) which it describes as a ‘great pioneering summary. [We] take up the challenge therein’, it adds. It sees the important role that DTM and Pambana played in Kenya:

We, the December Twelve Movement, have chosen to make our contribution by starting the first truly revolutionary people’s paper. Hitherto, no paper represented the wishes and activities of the poor and oppressed Kenyans correctly. This paper is dedicated to gathering, uniting, encouraging and protecting all those who would defiantly stand for our country’s and people’s true interests and who would sacrifice and fight towards our unity and victory

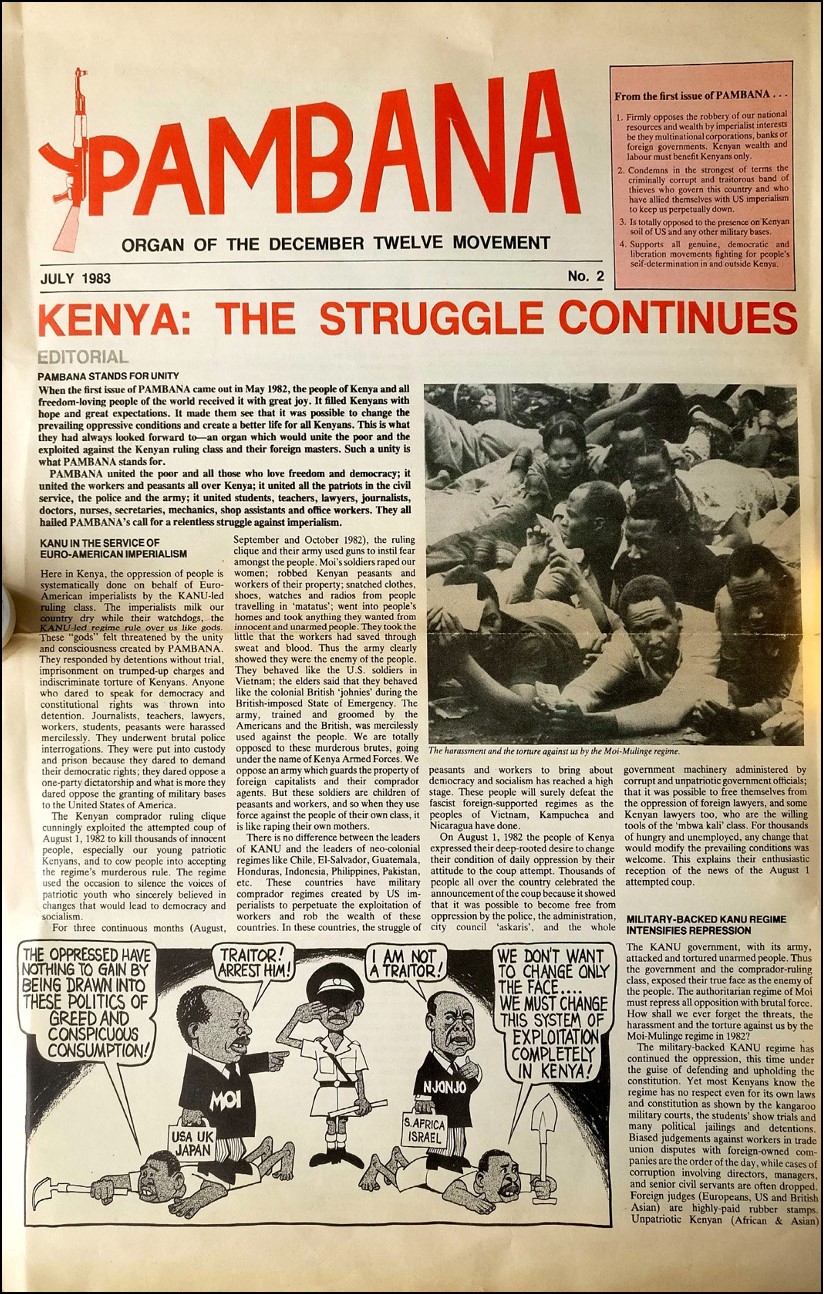

Pambana 2 (July 1983)

The Moi government used the coup attempt in 1982 to hit out at all those it saw as opposed to its rule. This included DTM leaders and members, but also many activists who were not members but were arrested and punished for political reasons. The government had read the first issue of Pambana and saw a danger to itself, which it then tried to kill by arresting the DTM leadership. However, it was not completely successful in this, and many of its cells continued the attacks on the government. It was some of the cells, which survived intact, that produced the second issue of Pambana in May 1983. The Editorial summed up events after the coup attempt of 1982:

The Kenyan comprador ruling clique cunningly exploited the attempted coup of August 1, 1982 to kill thousands of innocent people, especially our young patriotic Kenyans, and to cow people into accepting the regime’s murderous rule. The regime used the occasion to silence the voices of patriotic youth who sincerely believed in changes that would lead to democracy and socialism. Here in Kenya, the oppression of Kenya is systematically done on behalf of Euro-American imperialists by the KANU-led ruling class. The imperialists milk our country dry while their watchdogs, the KANU-led regime, rule over us like gods.

The main article explained the imperialist nature of the government in Kenya. DTM’s main plank is captured in the cartoon it carried in Pambana 2, shown here, emphasising the imperialist support for the Kenyan ruling class, the nature of bourgeoisie parliamentary politics, which was not for working people whose oppression and exploitation it ensured, and the need to change the system of exploitation.

Another section in Pambana was entitled, ‘Workers’ Struggles: The Current Situation’: under which it says ‘Workers Reject Government Sponsored Trade Unions’. It is noteworthy that while the government used all the colonial laws at its disposal to subdue the militant trade unions, particularly the East African Trade Union Congress under Makhan Singh, workers under militant shop stewards continued to strike and demand workers’ rights. The article continues:

Since May 1982, workers’ struggles in Kenya have developed to a higher combative level. Instead of workers trying to solve their economic problems through the corrupt governmentcontrolled trade unions, the workers have started to struggle against them. They have found out that these official trade unions are some of the instruments used to exploit and milk them.

This is an important development noted by Pambana. Workers were not defeated by the legal manoeuvring by the government to deprive them of their rights. The article went on to list strikes and action against police by militant workers. There then follows a section entitled ‘Women Lead the Struggle’. It concludes by talking about classes:

We do not want to discuss individuals but classes. Our concern is the people’s lives and the causes of their poverty, in other words, the exploitation they are subjected to. The lines have been drawn. Kenyan national politics has been divided into two camps. On the one hand are the comprador and their imperialist masters and, on the other, all the exploited masses and patriots of Kenya.

This was the key point in Kenya, which the ruling classes had kept hidden. It is to the credit of DTM that it brought the class issue to the forefront of the struggle for liberation. Nor did it forget Kenya’s militant history for independence and the example set by Mau Mau and Kimaathi. Under the heading, ‘Six Lessons from the Life of a Patriot’, Pambana reminded its readers the lessons taught by Kimaathi:

SIX LESSONS FROM THE LIFE OF A PATRIOT

Field Marshal Dedan Kimathi was born in Gatanga sub-location, Tetu Division Nyeri, on October 31, 1920. That was also the year when Kenya was declared a British colony after being ruled as a British protectorate and as a company property from 1888. Colonial rule against the people was imposed through the coercive machinery of the law, the army, and the police. People were forced to leave their land to become serfs and squatters in the big farms stolen from them by foreigners, and to become wage slaves in the new capitalist industries and plantations. The people of Kenya united in their opposition to every form of British colonial oppression. Kimathi grew up under these conditions of brutal colonial aggression on one hand and the resistance of the people against it on the other. He sided with the forces of resistance. His life is a lesson to us today as we struggle against neo-colonialism. Every revolutionary Kenyan must learn from his life.

- As a student, Kimathi organised night classes in which he passed on to the youth all he himself had learned during the day. In those days, not all young people were able to attend school. Because of teaching others, Kimathi became an example to be followed. He became a selfless agent for the spread of education among workers and peasants.

The life of a revolutionary must be an inspiration to others. A revolutionary must be prepared to educate the people politically and also learn from them

- In colonial schools, and even in his brief period in the colonial army, Kimathi courageously organised against brutality and tirelessly tried to raise the people’s consciousness about the need for unity against oppression.

Fighting against oppression is the duty and responsibility of every patriotic Kenyan.

- Even as a clerk and as a teacher, he continued fighting oppression and organising the people. Very often he found himself in trouble with his employers. He was forced to change jobs many times.

Patriotism demands sacrifice even if it means giving up one’s job and a comfortable family life. Revolutionary struggle is a lifetime commitment.

- He joined the Kenya African Union (KAU), which was then the democratic organisation of Kenyan people. He spoke out against colonialism. He was not afraid to show his real feelings of hatred for oppression. He knew he was fighting for justice.

A patriot must be imbued with hatred of all forms of oppression.

- He volunteered to work as a political education teacher for KAU. He was later elected the General Secretary of the Murang’a branch of this organisation. He worked hard day and night. No task was too big or too small.

For a revolutionary no task is too menial or too big. A revolutionary must be prepared to work hard day and night. The revolution is not a tea party

- Kimathi started his revolutionary struggle in his home area before he was given higher responsibility at the national level as a member of the KLFA (Mau Mau) High Command and later as the Commander-in-Chief of the KLFA. All revolutionary work starts at home or wherever one is.

If you cannot struggle against oppression wherever you are you will not gain the necessary experience for participating in and explaining our national revolutionary struggle.

A revolution starts with you wherever you are.

Pambana then took up the topic that is closest to the lives of working people: food. Under the heading, ‘The Politics of Food’, it exposed the hidden hands of imperialism in the form of the World Bank whose prescriptions for Kenya were the real reason for food poverty in the country. The article explained that it was the capitalist system that was the cause of food shortages and showed that countries that have adopted socialism were rapidly resolving their food problems

The Politics of Food

For many years now from newspapers and radio, we have been fed with government propaganda and that of the World Bank or other foreign “experts” that food shortages are a normal state of affairs in our country. They say there is not sufficient arable land in Kenya. They tell us that our population is too high and rapidly increasing and that not everyone can be fed. They tell us that we do not have enough Kenyan expertise. They tell us that capitalist agricultural production is the only type of agriculture possible. These are brazen lies spread by imperialists and their agents so that they can continue exploiting our country. The production process and the distribution of wealth is done in a way which enables the imperialists to make high profits. For a capitalist, maximising profit is the overriding concern. The aim is to invest as little as possible and with as little risk for the highest possible returns. A capitalist even makes profits from our misery. When the capitalist is a foreigner as is the case in our country, this means the continuous drainage of our wealth to foreign countries, thus making our country poorer and poorer as theirs become richer and richer. We must therefore know and understand that there are other systems of agricultural production, which would enable us to produce more food, sufficient for everyone and even have a surplus. There is no doubt this is possible. It has happened in other countries, which have dared to throw out imperialists and have afterwards adopted a system of agricultural production that puts people’s basic food requirements first. Let us have a look at some of these countries.

The article gave facts from these countries that have challenged capitalist food production and adopted socialism: China, Cuba, Nicaragua and North Korea. It concluded:

Only after getting rid of imperialist-backed oppression, shall we be able to take new directions in food production:

- Productive land must be in the hands of the masses;

- The people must be responsible for the production and distribution of food;

- Production of food crops and not cash crops must be given priority;

- Food should feed Kenyan people first before it is exported. Feeding people is more important than earning foreign exchange for importing BMWs, Volvos, Mercedes Benzes and other luxury items.

China, Cuba, Nicaragua, North Korea and many other socialist countries have banished hunger and starvation by adopting a different path of development. But in Kenya, despite the fact that we have some of the best agricultural land in the world, many poor people still suffer from hunger, malnutrition and as in the case of northern Kenya, from mass starvation. The majority of our people go hungry in a country where the weight-reducing industry (massageparlours, hormone-injections, weight-reducing clinics, saunas, etc.) for the overfed few is thriving. In Kenya, imperialist foreigners and a few rich come first, but in Cuba, China, Nicaragua and North Korea, the peasants and working people come first. In these countries, the people had to wage an armed struggle to free themselves from the stranglehold of imperialist-backed oppression before they could be responsible for their own food production. A relentless struggle against the alliance of the comprador mbwa-kali ruling class and Euro-American imperialism is the only way we Kenyans can use the wealth of our country to satisfy our own needs and banish hunger. The defeat of imperialism in its neocolonial stage is a necessary first step for our development as a Kenyan people

The article not only highlighted the main enemy of people — imperialism — but also showed DTM’s awareness about the political situation of Kenya and the way to overcome these challenges. Sadly, for working people in Kenya, Pambana did not survive after the second issue. It was the last newspaper to represent their interest. No similar paper has emerged to date. Such was the contribution of DTM and Pambana.

While the above publications from DTM show its stand, another perspective on its work is provided by Ong’wen in his forthcoming memoir:

During our struggle to register a student union, we forged political relationship with progressive forces — mainly from the academia — that had been organising in the underground. The December Twelve Movement (DTM) was already deeply entrenched. Some of us joined or established DTM study circles. The overt struggles gave us the platform to operationalise some of the programmes for covert plans. It also provided forums and arena for identification of ideologically motivated students who could be recruited into the underground movement. Contrary to the widely held view … underground opposition had been thriving since almost immediately after Kenyatta banned KPU [in 1969] and made the country a de facto one-party state.

History still waits for more records from those who were members or leaders of the Movement

Transition from DTM to Mwakenya: The Struggle Continues

The Moi government’s repression following the attempted coup in 1982 had grave consequences for DTM. Many of its leaders were detained, following the capture of the movement’s documents from one of the early detainees who had kept them — against the movement’s policy, as indicated by Mazrui and Mutunga (2014), quoted earlier. This was a major blow to the organisation.

However, many cells continued to function, but without the overall coordination that the DTM leadership had provided. Among these was the Kabete Cell, which continued its pioneering work by producing the play, Kinjikitile-Maji Maji and other activities under Sauti ya Wakutubi and Sehemu ya Utungaji.3 Other DTM cells also continued various activities and it is believed that some of them later emerged under the new name, Mwakenya.

At the same time, many DTM members in various countries around the world joined with local activists to form Umoja in 1987 in London. Umoja merged with Mwakenya in 1996 and re-energised it. It is thus true to say that DTM did not die in 1980s but continued to exist in Umoja and later in Mwakenya.4

It is in the context of the above history of DTM that the later history of Mwakenya-DTM, its ideology, organisation, tactics, and policies need to be seen. If they worked in Kenya even for a brief period, then that experience could be of value to other situations. Particularly relevant is the experience of the December Twelve Movement. What then are the lessons to be learnt from this pioneering underground resistance movement?

The first lesson is that it is impossible to organise against capitalism using its own playing field of the bourgeois parliamentary system, backed by bourgeois laws, courts and armed forces, not to mention its total control over education, mass media and culture. Any meaningful resistance has, of necessity, to organise and operate underground, with over-ground manifestations as appropriate.

Second, the organisation needs ideological clarity and awareness of what it is struggling against knowing its enemies and its friends, to put it another way. DTM, in many of its documents, set out its anticapitalist and anti-imperialist agenda, developing its ideas further in various areas of the economic, social, cultural, and political arena. Yet it shied away from stating clearly that it was aiming at socialism, although socialism was obviously its unstated aim. This is surprising, as the Kenya People’s Union had come out clearly for socialism before DTM-MK emerged. One requirement for a successful resistance movement is to state clearly what it is fighting for. While democratic parties may feel they cannot openly state their socialist ambitions, there was no reason for DTM to do so, as it was an underground movement. It thus lost an important opportunity to put socialism on the national agenda. There is perhaps a lesson here for other resistance movements.

Correct leadership is also required for putting into practice organisational policies. Again, various lessons can be learnt from the experiences of DTM, which ceased its activities because of the brutal attack on most of its leaders by the Moi government. Other leaders, within and outside Kenya could have tried to create a new structure under a new leadership to bring the underground cells together. Some did, indeed, try but the fact that they did not succeed indicates the need for better preparedness for such eventualities.

The need for a strong organisational structure that can meet changing circumstances was another requirement. While DTM had a strong central leadership, it operated in small local cells with its leaders linked up organisationally to the next level. This then led to the top leadership. Such a structure allowed it to maintain secrecy and made possible central leadership and local autonomy as a form of democratic centralism. Yet DTM cells were isolated from each other and lacked a central authority to organise and coordinate activities when its leaders were detained or exiled. Added to this was the fear that paralysed some in a position to address the new situation. Underground organisations organised for the need of security and secrecy need to pay attention to this experience of DTM. The need for ideological clarity among members was a priority. Regular study sessions formed part of cell meetings. Turning ideas into action then ensured that cadres had understanding as well as practical experience in all aspects of revolutionary work. Resources for study were held in different centres but a central underground library was also maintained.

An essential feature of underground work was to maintain close links with workers, peasants, students, professional groups, among others. DTM organised cells at all these levels, ensuring that information about people’s needs and conditions flowed to all levels in the organisation, which then helped to formulate policies and action plans to meet people’s needs. Communication with people was strengthened by the production and distribution of leaflets, pamphlets and the newspaper, Pambana. All this required organisation throughout the country via the cell structures. Also necessary were physical distribution and by mail in working class areas, through matatus and at food kiosks, among others. Similarly, regular pamphlets in Kiswahili and English analysing the local situation were written and distributed widely. Underground typing pools, duplicating and cyclostyling facilities were established as part of the information and communication strategy. These are basic requirements for an underground organisation.

Discipline among members was paramount. This is particularly so for recruitment and training of new members. DTM was strict in recruitment and admitted new members only after a long process of study and proven action in resistance activities at political, social or cultural levels. However, this practice was not followed under Mwakenya, at least in the initial stages. This allowed members who did not have ideological clarity and experience to capture leadership positions, bringing liberalism into the organisation. The need for constant struggles for a clear political line is essential if resistance is to succeed.

It is to the credit of DTM members in exile that they continued the struggle in countries of their exile. Various organisations in different countries came together to form Umoja in 1987 in London. Umoja became an important part of Mwakenya after that. An overseas partner is a useful asset to support local actions.

Taken as a whole, the work of DTM and Mwakenya provides a model to deal with the iron grip of imperialism in Africa. This is particularly relevant as the so-called colour revolutions tend to be instigated or infiltrated by imperialism.

There are thus lessons to be learnt from the collapse of the DTM and Mwakenya under intense attacks, both political and physical, from the Moi government, with its notorious torture chambers at the Nyayo House in Nairobi. Some of its internal weakness as well as intense attacks, from an enemy armed to the teeth, played their part in their decline. Perhaps there is a lesson here that confronting an armed enemy with just political means — underground or overground — is not a formula for success. Mass mobilisation of people, together with other tactics, would have to be included in the anti-capitalist arsenal.

While it is not possible to predict the future direction of events in Kenya, it seems likely that the experience of December Twelve Movement and Mwakenya will be of increasing relevance, just as that of Mau Mau from an earlier period has been. Mau Mau’s and DTMMwakenya’s message of resistance at every level needs to be on the agenda, too. It is for this reason that imperialism and comprador policies have conspired to keep their documents hidden; it is for this reason that activists today need to learn the real history of Kenya’s resistance to capitalism and imperialism. It is fortunate that Ukombozi Library in Nairobi has set up the Kenya Resistance Archives to collect and disseminate material from DTM, Mwakenya and Umoja, among others.

The attacks on socialism in Kenya by imperialism were by no means isolated incidents. Almost every country which has struggled against capitalism and imperialism has faced intolerable attacks from imperialism in the form of economic sanctions, covert and overt support for real or created opposition, assassinations, coups instigated from USA and supported by its allies in Europe, Canada and Australia, drone attacks on leaders and strategic targets… the list is endless and stretches over decades. Vietnam stood against European and USA attacks for decades, as is Cuba doing today.

Libya, Iran, Malaysia, Indonesia and Latin America as a whole have been attacked when they sought independence from imperialism and its agencies; millions of activists have been killed by imperialism to suppress socialism. Palestine stands out as perhaps the most important example of imperialist attacks when the entire country has been captured by Israel with the support of USA.

It is not only ‘small’ countries that have been under attack. China and Russia face daily attacks now that imperialism has identified them as its greatest ‘enemies’. Nor was the Soviet Union free from such attacks. Tickle (2021) reports on a situation like that in Kenya under Jomo Kenyatta and Tom Mboya, who had agents of USA ‘guiding’ them in implementing capitalism. Socialism in USSR faced even bigger challenges as Tickle (2021) records:

The first Russian president, Boris Yeltsin, was surrounded by “hundreds” of CIA agents who told him what to do throughout his tenure as leader. That’s according to Ruslan Khasbulatov, the former chairman of Russia’s parliament

That puts the past and the present of Kenya in its global context. The Two Paths — to socialism or capitalism —which were the choice at independence, are still the choice today. DTM chose socialism and faced the wrath of imperialism. A more intensive resistance movement, learning lessons from the past, is needed to meet today’s challenges.

References

Cheche Kenya (1982): InDependent Kenya. London: Zed Press.

Durrani, Shiraz (2008): Information and Liberation: Writings on the Politics of Information and Librarianship. Nairobi: Vita Books.

Durrani, Shiraz (2014): Progressive Librarianship: Perspectives from Kenya and Britain, 1979-2010. Nairobi: Vita Books.

Hornsby, Charles (2013): Kenya, A History Since Independence. London: I. B. Tauris.

Kinyatti (2014): Mwakenya, the Unfinished Revolution. Nairobi: Mau Mau Research Centre.

Kinyatti, Maina wa (2019): History of Resistance in Kenya. Nairobi: Mau Mau Research Centre

Mwakenya (1992): Hata Bila Moi, Umoi Tunapinga! Msimamo Rasmi wa Mwakenya Kuhusu Hali ya Mambo Nchini. Ngugi wa Thiong’o, Kwa niaba ya MWAKENYA. January 1992.

Maxon, Robert M and Thomas P. Ofcansky (2000): Historical Dictionary of Kenya. 2nd ed. Lanham, Maryland, USA: Scarecrow

Mazrui, Alamin and Mutunga, Willy (2014): Confidential comments following the launch of Maina wa Kinyatti’s book, Mwakenya: The Unfinished Revolution (2014).

Ong’wen, Oduor (Forthcoming): Stronger than faith: My journey in the quest for justice in repressive Kenya.

Pambana, Organ of the December Twelve Movement. No. 1, May 1982.

Wachira, Kamoji (2019): Kamoji Wachira interviewed by Onyango Oloo (23-09-2019).